Obesity & Weight Loss Surgery / Bariatric Surgery

Twenty-five percent of the adult Australian population are obese (body mass-index (BMI) greater than 30 kg/m2). Obesity is a significant risk factor for the metabolic syndrome and other diseases.

Lifestyle modification through diet and exercise is essential for any weight-loss strategy to work. Unfortunately diet and exercise alone rarely succeed in providing durable and significant weight-loss. Surgery has become more widely accepted, not because it is a “quick fix” or an “easy way out”, but because there is the highest level of evidence supporting its role in significantly reducing weight, improving health, and reducing the risk of premature death.

Bariatric surgery is indicated for morbidly obese patients (BMI>40) who have failed non-surgical weight loss. In this patient group there is good evidence that it improves quality of life and prolongs survival. Surgery is also indicated in those with a BMI>35 with significant obesity related co-morbidities.

Who should consider surgery?

BMI>40 (morbid obesity)

BMI>35 with significant health problems related to weight

Age 18-65

Previous attempts at weight loss

Fit for surgery (no end-stage organ failure – heart, lung, liver)

Committed to lifestyle change

Realistic expectations

Full understanding of all procedures and their risks

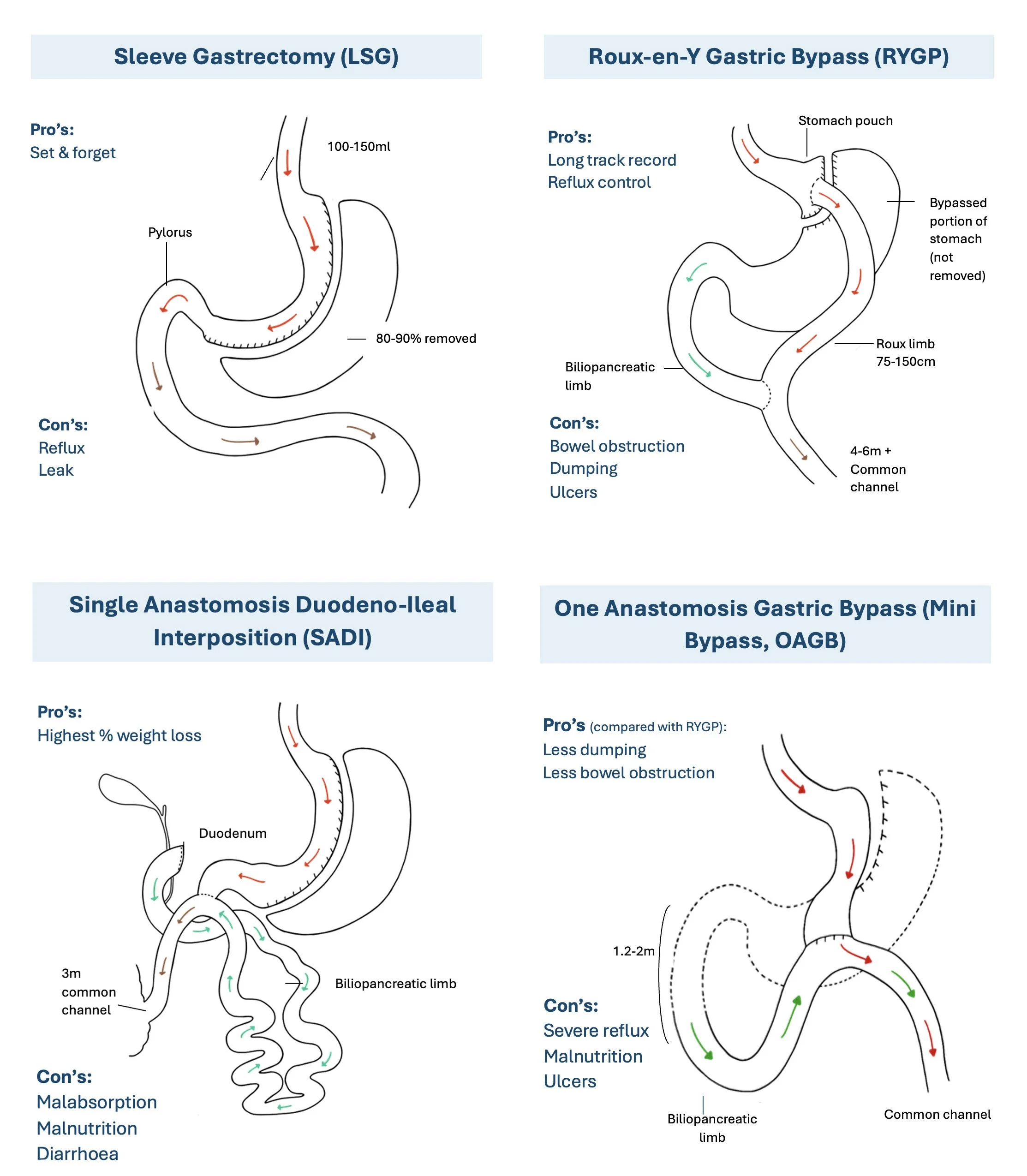

What types of bariatric surgery can be performed?

There are three bariatric procedures commonly performed in Australia: the adjustable gastric band (AGB), the roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGBP), and the sleeve gastrectomy (SG). These procedures are generally performed laparoscopically, although open surgery is sometimes used in the revisional setting. All three operations act primarily by restricting the volume that can be eaten. Primarily malabsorptive operations, such as the bilio-pancreatic diversion, have been associated with significant morbidity and mortality and are not routinely performed in this country. The vertical banded gastroplasty (“stomach stapling”) is now obsolete.

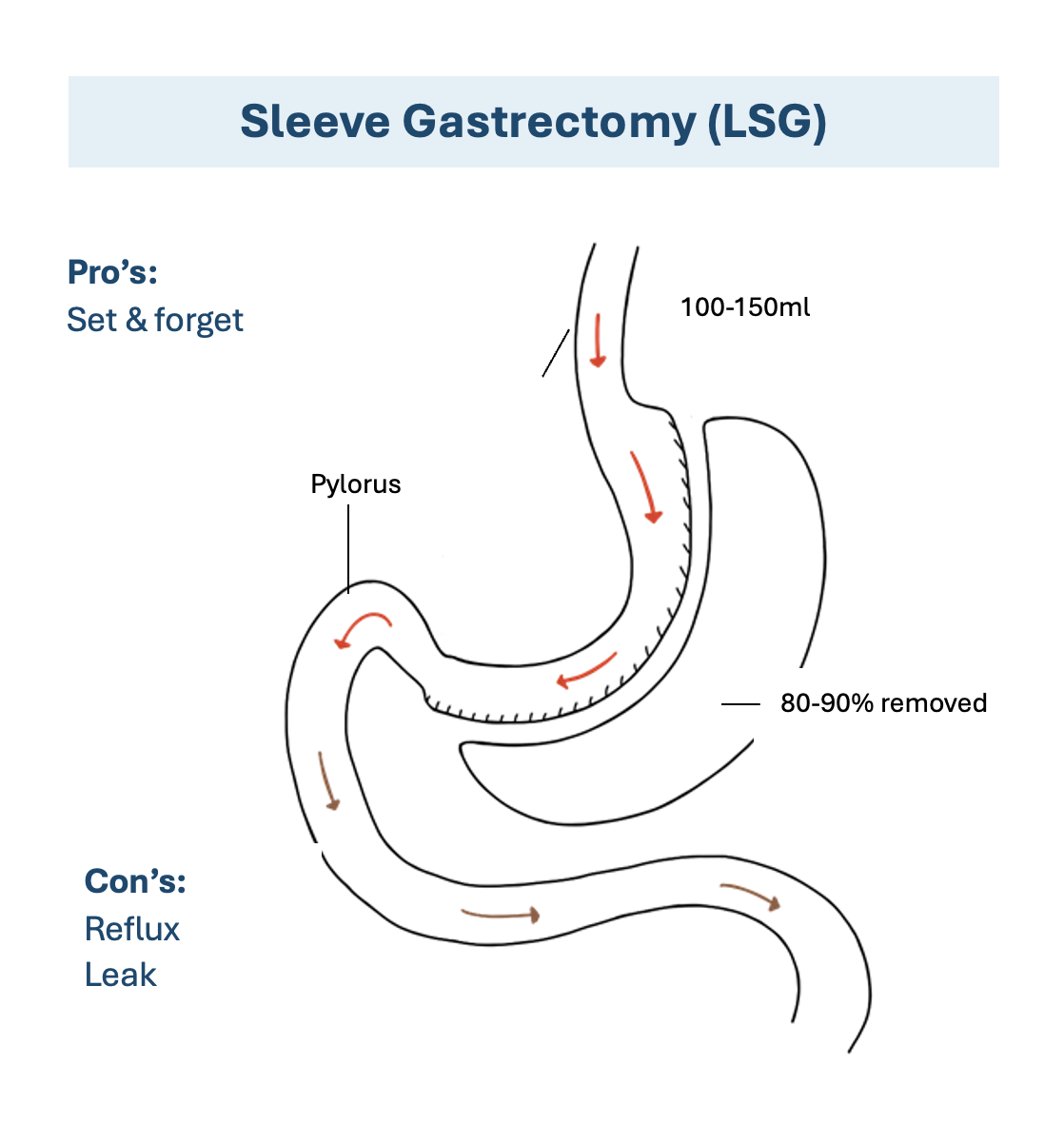

Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

Laparoscopic SG is a relatively new procedure. It originated as the first stage of a two stage procedure in the super-obese, but is now increasingly performed as a definitive bariatric operation. It is the only non-reversible bariatric operation: it involves removal of the greater curvature of the stomach leaving a narrow gastric tube. The fundus of the stomach is the primary site for ghrelin secretion. Ghrelin is the only identified orexigenic hormone (“hunger hormone”) and SG has been shown to lead to sustained reduction in ghrelin levels and reduced hunger compared to other bariatric operations. Karamanakos et al enlisted 32 patients in a double blind RCT comparing SG with RYGBP and found better weight loss in the SG group at one year (70% vs 60%). Himpens et al compared SG with AGB (80 patients) and found better weight loss at three years (66% vs 48%). The long term results of the SG are yet to be published: gastric reflux and dilatation of the sleeve have been reported, and the incidence of weight regain is not yet known. The SG sits between the AGB and RYGBP in terms of operative morbidity: anastomotic leak from the long gastric staple line has been reported in up to 1% of cases, however there is no potential for procedure-related complications once convalescence is complete (cf. RYGBP where there is up to a 5% lifetime incidence of internal hernia requiring re-operation). This may make the SG an appropriate choice for people living remotely.

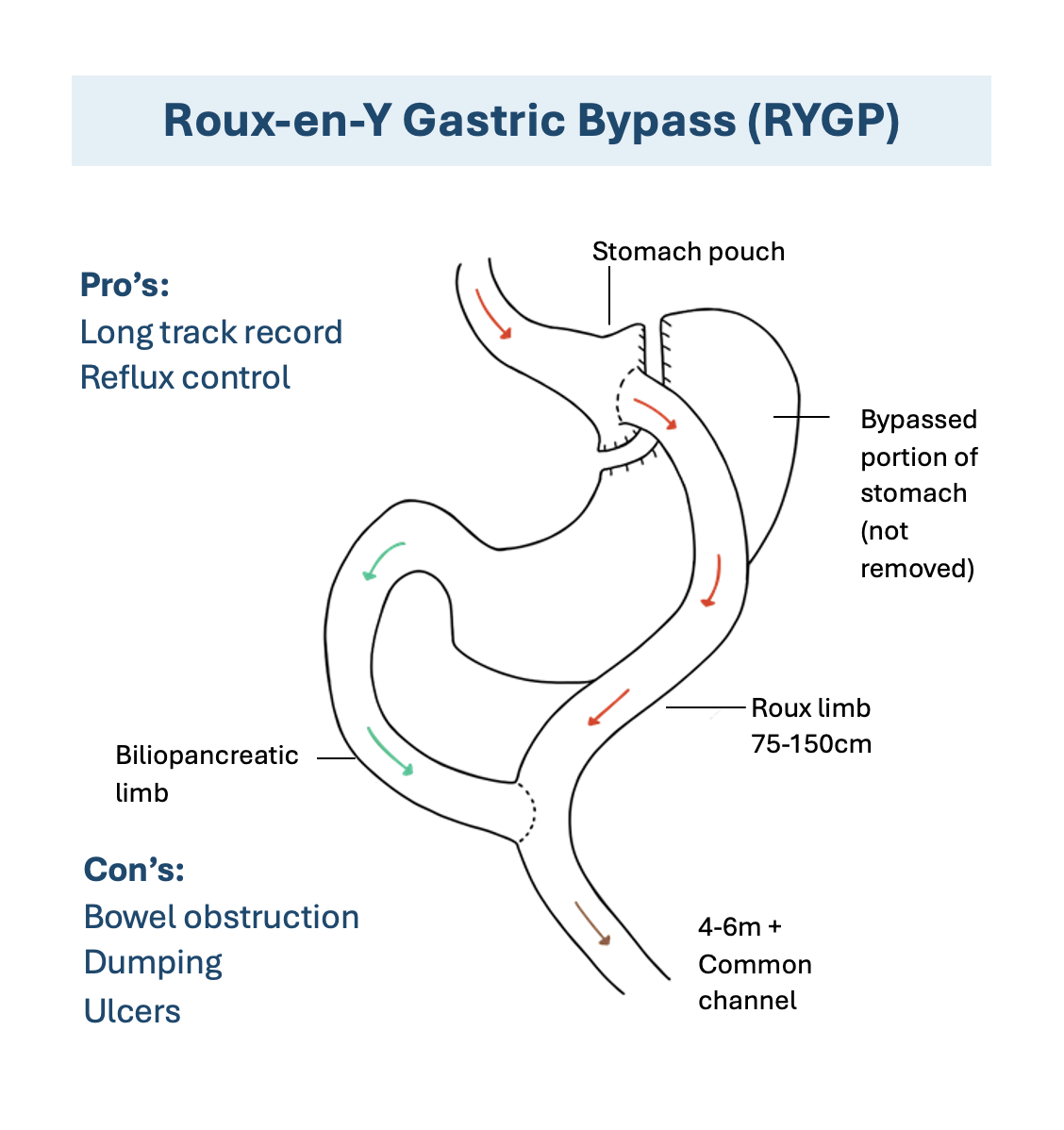

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGBP)

The RYGBP is the most established bariatric procedure; gastric bypass for weight loss has been performed since the 1960s. Predicted weight loss averages 65% EBW, mostly by 18 months post-op and there is a sustained reduction of 30% of total body-weight at 10 years. This sophisticated procedure combines two powerful weight loss mechanisms: restriction and malabsorption. During the surgery, your surgeon creates a small stomach pouch about the size of an egg, which dramatically limits the amount of food you can eat at one time. The small intestine is then rearranged in a distinctive Y-shaped configuration, bypassing the lower portion of your stomach and the first section of your small intestine (duodenum). This rerouting means that food travels directly from your new small stomach pouch into the middle section of your small intestine, reducing the absorption of calories and nutrients.

While the primary effect of surgery is to restrict the volume of food eaten, undigested food entering the roux limb can lead to a dumping syndrome which acts as a deterrent to over-eating calorie rich foods. Bypass of the proximal small bowel leads to a reduction in putative diabetogenic factors which leads to rapid resolution of type two diabetes, even before significant weight-loss occurs. Remission of diabetes is seen in 75-95% of patients.

The complications of surgery (anastomotic leak, stomal ulceration, internal hernia) are potentially life threatening. Nutritional sequelae such as iron deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, osteoporosis and gallstone formation occur with greater frequency than with the AGB, and mandate careful follow-up.

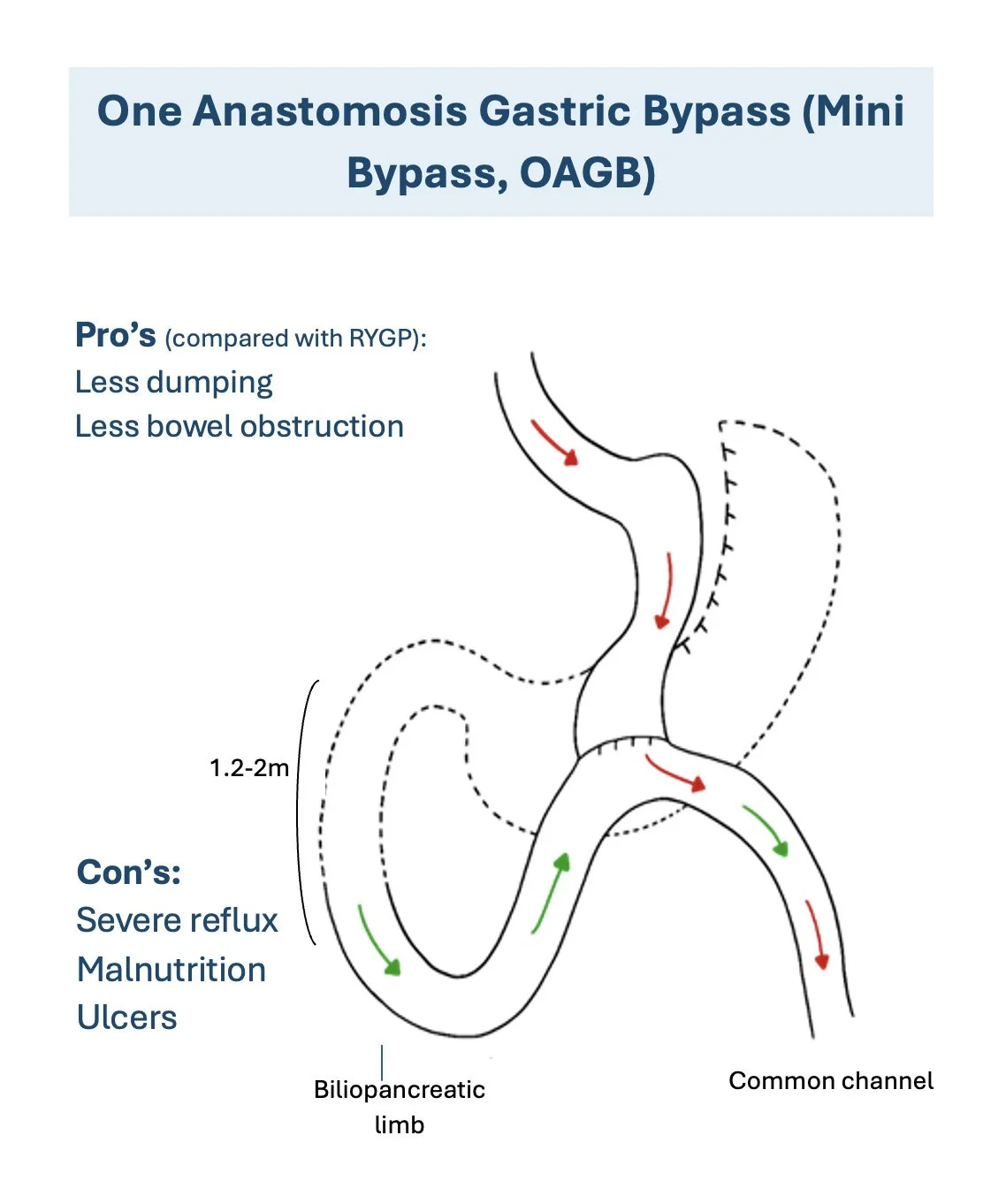

Mini Gastric Bypass (MGB)

The Mini Gastric Bypass (MGB), also known as One Anastomosis Gastric Bypass (OAGB), is a modern bariatric procedure that offers the benefits of traditional gastric bypass surgery through a simplified, streamlined approach. This innovative technique combines both restrictive and malabsorptive mechanisms to achieve significant weight loss, but does so with fewer surgical connections than the traditional Roux en Y procedure.

During MGB surgery, your surgeon creates a long, narrow stomach pouch by dividing the stomach lengthwise, leaving you with a tube-shaped stomach approximately the size of a banana. This new stomach pouch is then connected directly to the small intestine approximately 150-200 centimeters (about 6 feet) from its beginning, bypassing a significant portion of the small intestine where calories and nutrients are normally absorbed.

The "mini" designation comes from the procedure's simplified design, requiring only one surgical connection (anastomosis) compared to the two connections needed in traditional Roux en Y surgery. This streamlined approach often results in shorter operative times and potentially fewer complications, while still delivering excellent weight loss results. The procedure has gained significant popularity worldwide and is now recognized as a safe and effective alternative to more complex bariatric surgeries.

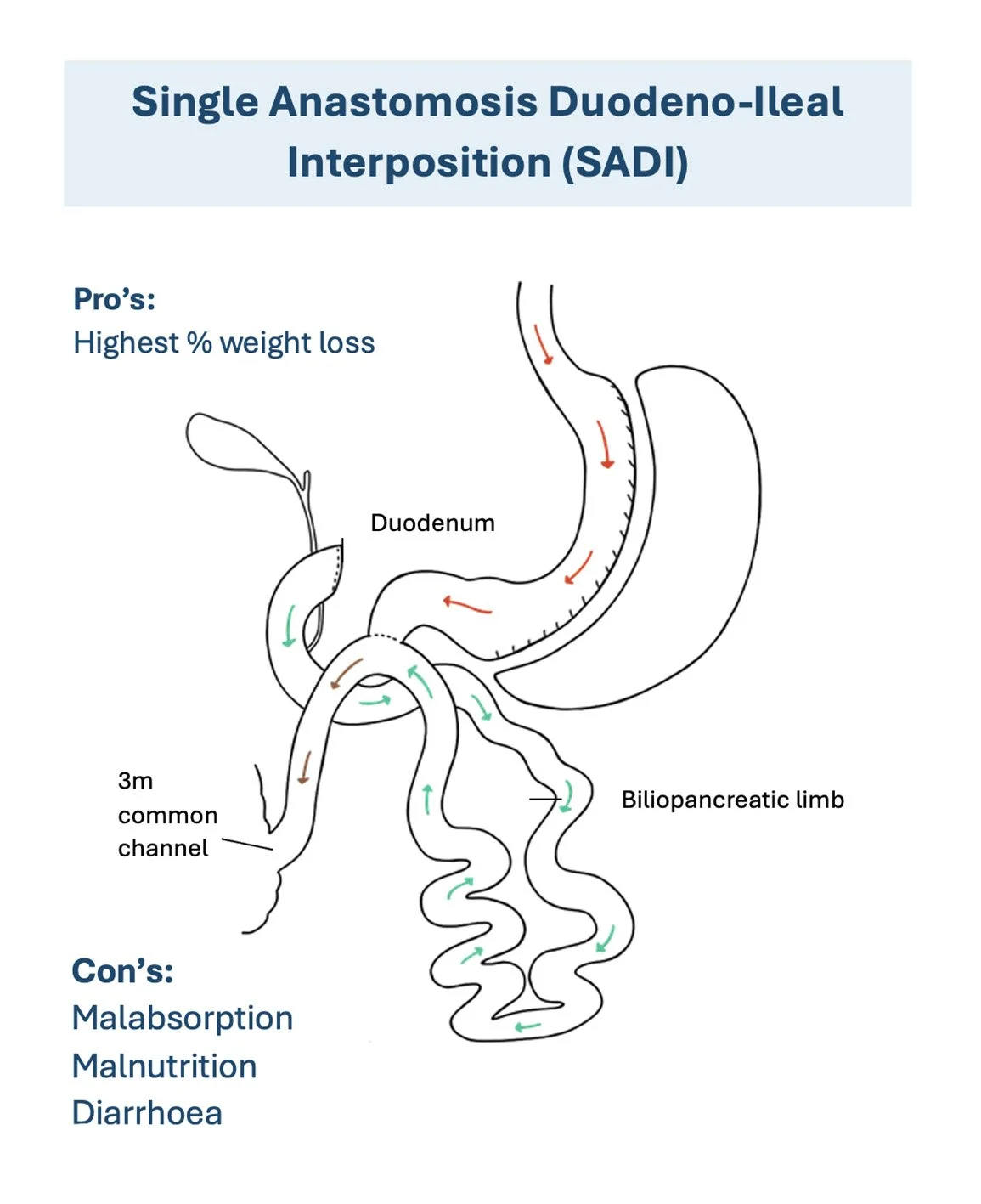

Single Anastomosis Duodenal-Ileal Interposition (SADI)

Single Anastomosis Duodenal-Ileal Interposition (SADI) is an innovative and powerful bariatric procedure that represents the newest advancement in weight loss surgery. This sophisticated technique combines the restrictive benefits of a sleeve gastrectomy with the malabsorptive advantages of intestinal bypass, creating one of the most effective surgical options available for patients with severe obesity or complex metabolic conditions.

The SADI procedure is performed in two distinct components. First, your surgeon performs a sleeve gastrectomy, removing approximately 80% of your stomach to create a narrow, banana-shaped stomach sleeve that restricts food intake. Second, the surgeon creates a single connection (anastomosis) between the first part of your small intestine (duodenum) and the final portion of your small intestine (ileum), bypassing the majority of the small intestine where nutrient absorption typically occurs.

Adjustable gastric band (AGB)

The AGB accounts for 95% of bariatric surgery in Australia. This popularity relates to its perceived safety. There is no doubt that the AGB is the safest weight-loss operation (Table 1), but revisional surgery is required at a rate of 1-2% per year. This is mostly for slippage of the stomach under the band, erosion of the band into the stomach or inadequate weight-loss. Revisional bariatric surgery is more complex than primary surgery and there is a four-fold increase in morbidity and mortality.

Predicted weight-loss with the AGB is 50% of excess body weight (EBW) over three years. This is achieved with careful follow-up to ensure that the degree of restriction is appropriate. The AGB works by transiently obstructing the passage of solid foods, which stretches the gastric wall above the band thereby signaling satiety. An AGB that is too tight leads to maladaptive eating: softer textured foods are favoured as solids precipitate pain, reflux or regurgitation. This bypasses the satiety mechanism leading to inadequate weight-loss, and probably increases the rate of AGB slippage due to recurrent vomiting. Regular dietetic review is mandatory to monitor nutritional intake and help facilitate changes in eating behaviours (e.g. avoiding grazing, eating slowly, eating to satiety rather than fullness).

Four percent of the Australian population currently have diabetes and this number is predicted to rise significantly. Bariatric surgery cures a significant proportion of type two diabetes. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Dixon et al (10) compared the AGB to conventional therapy in 60 obese patients (BMI 30-40). Over a two year follow-up period 73% of the surgically treated group achieved remission compared to 13% of the conventionally treated group. The same group have published the cost-effectiveness of surgery as a treatment for type two diabetes and concluded that it is a dominant intervention: one that saves money ($2400) and prolongs life (1.2 quality-adjusted life-years).

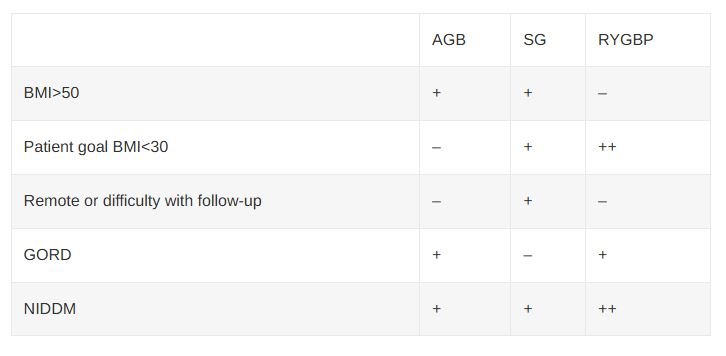

Bariatric surgery in Australia is still dominated by the AGB, and with good reason, as Australia’s published results for weight-loss with the AGB are the best in the world. The AGB is a prosthetic device and a certain proportion will require revision. As the cohort of patients requiring revisional surgery grows, so will the prevalence of RYGBP. There are no large multi-centre trials comparing the various operations as primary procedures, and these are unlikely to happen until the surgery becomes widely available in the public sector. A tailored approach to the choice of primary operation based upon patients’ expectations of weight loss, ability to attend follow-up, co-morbidities, presence of reflux and initial BMI may lead to a reduction in the need for revisional surgery (table 2).

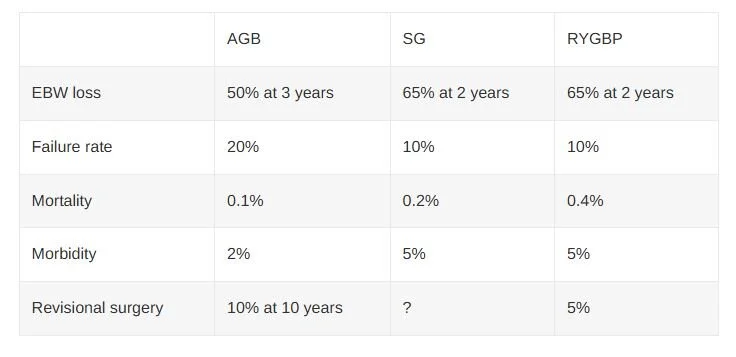

Table 1. Efficacy and risk of bariatric surgery. Failure rate refers to failure to achieve loss of 50% EBW.

Table 2. Factors influencing choice of operation

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: Summary of Results, 2004-05. Canberra: ABS; 2006. ABS Cat. No.:4364.0

Colquitt JL, Picot J, Loveman E, Clegg AJ. Surgery for Obesity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Volume (4), 2009

Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724-37.

Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741-52.

Medicare Australia Statistical Reporting. URL: www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/statistics accessed April 2010

Christou NV. Impact of Obesity and Bariatric Surgery on Survival. World J Surgery (2009) 33:2022-27.

Brolin RE. Cody RP. Weight loss outcome of revisional bariatric operations varies according to the primary procedure. Annals of Surgery. 248(2):227-32, 2008 Aug

O”Brien PE. Dixon JB. Brown W. Schachter LM. Chapman L. Burn AJ. Dixon ME. Scheinkestel C. Halket C. Sutherland LJ. Korin A. Baquie P. The laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (Lap-Band): a prospective study of medium-term effects on weight, health and quality of life. Obesity Surgery. 12(5):652-60, 2002 Oct

Buchwald H. Estok R. Fahrbach K. Banel D. Jensen MD. Pories WJ. Bantle JP. Sledge I. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Medicine. 122(3):248-256.e5, 2009 Mar

Dixon JB. O”Brien PE. Playfair J. Chapman L. Schachter LM. Skinner S. Proietto J. Bailey M. Anderson M. Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 299(3):316-23, 2008 Jan 23.

Gan SSH, Talbot ML, Jorgensen JO. Efficacy of surgery in the management of obesity related type II diabetes mellitus. ANZ J. Surg. 2007; 77: 958-62.

Rubino F. R”bibo SL. del Genio F. Mazumdar M. McGraw TE. Metabolic surgery: the role of the gastrointestinal tract in diabetes mellitus. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 6(2):102-9, 2010 Feb.

Regan JP. Inabnet WB. Gagner M. Pomp A. Early experience with two-stage laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as an alternative in the super-super obese patient. Obesity Surgery. 13(6):861-4, 2003 Dec.

Kojima M. Hosoda H. Date Y. Nakazato M. Matsuo H. Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 402(6762):656-60, 1999 Dec 9.

Nakazato M. Murakami N. Date Y. Kojima M. Matsuo H. Kangawa K. Matsukura S. A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 409(6817):194-8, 2001 Jan 11.

Karamanakos SN. Vagenas K. Kalfarentzos F. Alexandrides TK. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective, double blind study. Annals of Surgery. 247(3):401-7, 2008 Mar.

Himpens J. Dapri G. Cadiere GB. A prospective randomized study between laparoscopic gastric banding and laparoscopic isolated sleeve gastrectomy: results after 1 and 3 years. Obesity Surgery. 16(11):1450-6, 2006 Nov.

What will happen at my first appointment?

You will see the nurse who will go through your medical history and then see the surgeon. You may be referred to have some blood test, see a dietician, have a gastroscopy and/or see a psychologist. Once these have been completed, you will return to see doctor approximately 4-6 weeks after your first appointment.

Do I really need to see a psychologist?

Yes, if at the appointment you were instructed to see a psychologist you must undertake this task before your next appointment with Dr Karihaloo. If you have a psychologist that you already actively see, please discuss this with us. If you do not, we have psychologists that we refer to who specialist in bariatric patients undergoing weight loss surgery and we will give you the instructions at the first appointment.

How much will weight loss surgery cost?

You will be approximately out-of-pocket $6000 after everyone’s fees. This includes the surgeon, anaesthetist, assistant and any pathology fees. Initially you will need to outlay more than $6000 and claim from Medicare and your private health fund. This does not include your hospital excess if you have one.

See here for more: Informed Financial Consent

Bariatric & Weight Loss Surgery across Lake Macquarie, Newcastle, Hunter Valley, Gateshead

Our surgeons see both public and private patients in the Surgery Central consulting rooms in the Lake Macquarie Specialist Medical Centre and operate in both public and private hospitals.